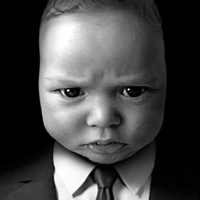

Uncle

Photo by Osman Rana on Unsplash

My uncle was a farmer. When I was a boy, he would let me drive his tractor. There is something you should know about boys and tractors. If you let a boy drive a tractor, it may not seem like much to you, but he will remember that moment forever. I remember my uncle letting me drive his tractor. As clearly as I remember my name.

I also remember there was a short hedge fence in front of my uncle’s house. On a summer day, I would complain it’s too hot and how I wish I could swim in the sea. But there was no sea to swim in. We were 500km from the sea. My uncle would pick me up, hold me above the hedge fence and say: “Swim!” And I would pretend to “swim” in the hedge.

That’s mostly what I remember about my uncle.

When I grew up, we lost touch. I moved somewhere far. Just a bit too far, it seemed. I also lost touch with his sons, my older cousins, and never really got to know their kids. I only saw a few snapshots of them, ranging from babies to adults, taken on rare occasions that brought us together for a few hours. In between those hours, we were strangers.

I only heard stories about them. Most of them bad. Who was mean to whom. Who did this wrong and who did that wrong. You know. What families talk about when they lose touch.

I imagine they heard stories about me and I bet I was mean and did something wrong, too. And if they didn’t hear such stories, they probably should have. Frankly, I wouldn’t mind. Or care. Just like they probably don’t. And shouldn’t.

I’ve never heard anything bad about my uncle, though.

The last time I saw him was right before this fucking pandemic. He was very old and in bad shape. He could barely recognise me. But he stared at me and smiled. And I knew it was still him. And I didn’t feel sad.

Was it because I didn’t care? Or because I had adopted a more stoic view of the world and thought: “This is just life”? I don’t know.

My uncle died two days ago. I was at his funeral today. A warm, sunny day, almost as if to spite the sad occasion and February in The Balkans. Lots of people attended.

I observed the latest snapshot of my cousins and their families. All the children are adults now. Some of them expecting. They are all beautiful. They all seem to be doing well in life.

There we were, sinners, all imperfect in our own way, sobbing in front of a photo of my uncle. On that photo, he is smiling. His signature smile. Disconnected decades ago, we now share almost nothing except some genes and this sadness.

Pavle, a late patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church, once said that, when a man is born, everybody is smiling while he is crying. But he should lead such a life that, when he dies, everybody is crying while he is smiling. I’ve been telling people this was my favourite quote, never imagining that, one day, I will get to witness it.

As the coffin was being lowered into the grave, the priest said one last prayer. Something about no man being able to go through life without sin and an appeal to God to forgive those of my uncle.

One of my nieces, a stranger to me, crying almost hysterically, was barely able to catch enough breath and interject quietly:

“There is nothing to forgive.”